Bernini’s Models: Displaying Process in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Bernini: Sculpting in Clay

Metropolitan Museum of Art: October 3 – January 6, 2013

Also: Kimbell Art Museum: February 3 – April 14, 2013

Curated by Ian Wardropper, Anthony Sigel, and C.D. Dickerson, with Paola D’Agostino

![Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Italian, Naples 1598-1680 Rome), Model for the Lion on the Four Rivers Fountain, ca. 1649-50. Terracotta. 125/8 x 23¼ x 12 5/8 in. (32 x 59 x 32 cm) Accademia Nazionale di San Luca, Rome. Photo by Zeno Colantoni, Rome [LEONE ©ZC-041]](http://theafproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/1.-Bernini_Model-for-the-Lion-on-the-Four-Rivers-Fountain_Side-View-1_Rome-1024x669.jpg)

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Italian, Naples 1598-1680 Rome), Model for the Lion on the Four Rivers Fountain, ca. 1649-50. Terracotta. 125/8 x 23¼ x 12 5/8 in. (32 x 59 x 32 cm) Accademia Nazionale di San Luca, Rome. Photo by Zeno Colantoni, Rome [LEONE ©ZC-041]. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

There is a Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) that is pervasively known: the baroque artist that created dynamic sculptures, compellingly describing the appearance of textures and making the monumental seem fluid and ethereal. The exhibition Bernini: Sculpting in Clay invites us to consider a different side of the artist. Here we encounter not the tremendous and spectacular marbles, but perishable terracotta models and discrete preparatory drawings. Neither is here displayed the emphasis on carefully described surfaces but, rather, the immediate encounter with the ephemeral and the utilitarian.

Thirty drawings and thirty-nine terracotta models are shown together for the first time, presenting a look into Bernini’s creative process. It is this interest in process that makes Bernini: Sculpting in Clay a remarkably interesting exhibition. Preparatory works are often presented as autonomous works of art in their own right which, at times, neglects the way that those objects operated in their original contexts. Rather than isolating the drawings and models, the curators of Bernini: Sculpting in Clay draw attention to the rich networks of relationships that exist between the different models, the drawings and the finished work. Though perhaps certain orthodoxy hinders the exhibition from developing these interrelations to their profound logical conclusions, it is nonetheless significant that it embraces an active contemplation on the manifold activities that buttress a final product.

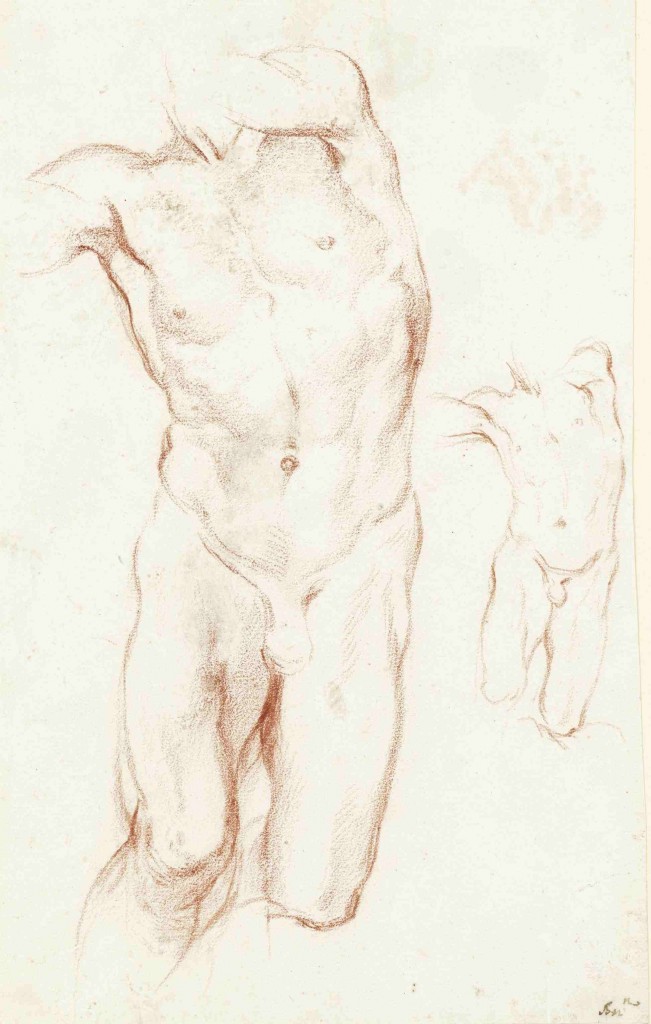

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Italian, Naples 1598-1680 Rome), Study for Daniel, ca. 1655. Red Chalk. 14 7/8 x 9 3/8 in. (37.8 x 23.8 cm). Museum der Bildenden Künste, Leipzig. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Examples of this interest are the preparatory works for St. Longinus in Saint Peter’s Basilica. By visually juxtaposing the drawings to the clay models, and by placing them adjacent to a large photograph of the sculpture, the viewer can freely interact between the objects and an image of the famous marble. Though it is possible to see the different drawings and models as individual steps, and indeed as chronological indicators, it is also significant that the exhibition does not strongly force a sequential approach. As these objects are not displayed linearly, the viewers remain free to pivot and rotate in order to consider how Bernini used different media to approach different problems in the composition and assembly of the sculpture. What these pieces underscore is the ways in which Bernini negotiated specific technical and aesthetic problems, and how he broke down the creative process into separate concerns. Here as well, as in the rest of the exhibition, the addition of large black and white photographic evidence of the sculpture is a laudable choice, helping the viewer to situate the models and sketches without presenting the overpowering gravity of the final artwork.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Italian, Naples 1598-1680 Rome), Daniel in the Lion’s Den, ca. 1655. Terracotta. 15 3/8 x 8 11/16 x 5 11/16 in. (41.6 x 22 x 14.5 cm). Musei Vaticani, Vatican City. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A highlight of the exhibition is the work done for the fountains in the piazza Navona, especially the Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi. It is for this work that the exhibit displays the iconic figure of the large lion, which is perhaps the most complete and finished of all the pieces shown. A large wooden model made for this fountain, although weathered, is also noteworthy. It makes manifest the multimedia aspect of the creative process in Bernini’s workshop, and it reminds us of the importance of three-dimensional ligneous models in architecture, a practice that often does not receive its deserve attention in curatorial and academic practices.

The exhibition articulates its most interesting concerns in those moments in which the practical coexists with the aesthetic, where the pragmatic interest of building operates along aesthetic sensibilities. At the same time, there is a palpable lack of information regarding the technical means of construction, and often the exhibition begs the question of how these models were translated into the monumental and finished works of art we encounter in Rome. In other words, in emphasizing the germ of an artistic idea, the exhibition gives the pragmatics of construction a wide berth. What is precisely noticeable, then, is the ways the exhibition both opens up the notion of process and dispels it by focusing only on a very specific type of process, namely the creative landmarks of Bernini’s hand. In this sense, process becomes aestheticised and dematerialized.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Italian, Naples 1598-1680 Rome), Angel with the Superscription (detail), ca. 1667-68. Terracotta 14¼ x 7 5/8 x 7 1/8 in. (36.3 x 19.5 x 18 cm). Museo Nazionale del Palazzo di Venezia, Rome. Photo by Anthony Sigel. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Of course, it is indisputable that the models show Bernini’s artistic ability. The economy with which the artist is capable of shaping figures and voluminous fabrics is certainly remarkable. In fact, it is precisely this sculptural quick, painterly style that so clearly defines the sculptural models: Bernini’s strokes do not describe accurately; they articulate the indeterminate in transitory studies of spirited matter. For this reason, the true highlights of the exhibition are not those models and drawings that present a most thorough state of completion but, rather, those juxtapositions in which fragmentary pieces shows the ways the artist and his workshop contemplated the problems and choices inherent in the process of artistic creation. By virtue of this emphasis on process, as well as the artistic qualities and uniqueness of the displayed objects, Bernini: Sculpting in Clay is an appealing, elegantly arranged exhibit that reminds us of the many caveats and circumstances that artists face.

For more information about the exhibition, please click here.

Javier Berzal de Dios is a History of Art Ph.D. Candidate at the Ohio State University.